Single decision trees overfit easily and produce unstable predictions. Change your training data slightly and you get a completely different tree. Yet somehow combining many trees creates some of the most powerful machine learning models available. How does that work?

Mastering ensemble methods like random forests and gradient boosting gives you the tools that win machine learning competitions and power production systems. These algorithms consistently outperform simpler models across a huge range of problems. Understanding when to use each one helps you build better solutions faster.

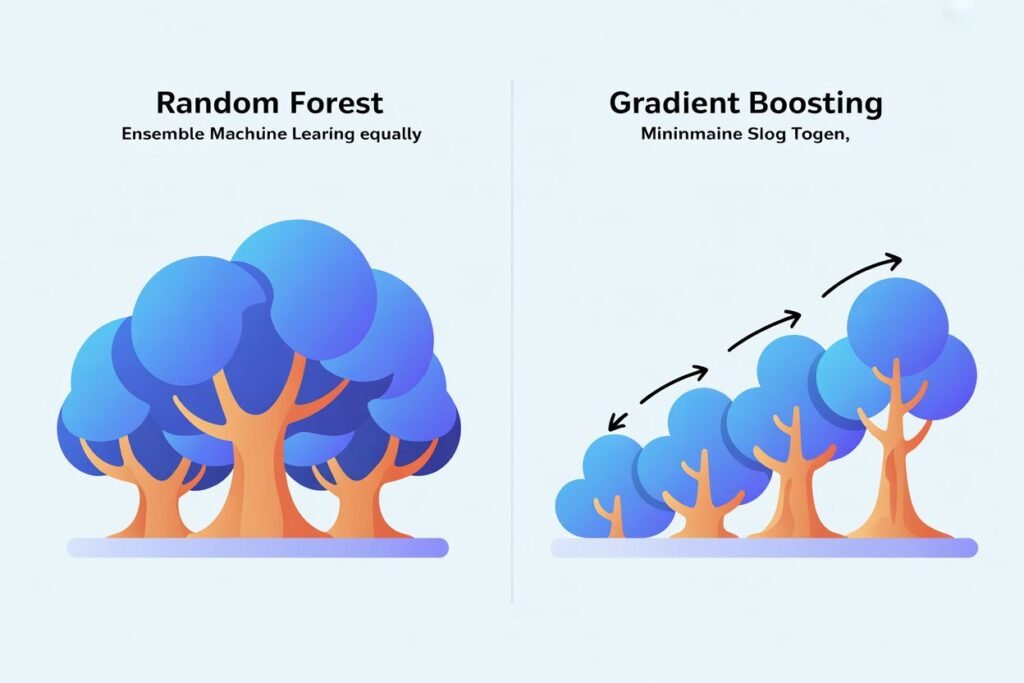

Random forest vs gradient boosting represents two different philosophies for combining trees. Random forests train many trees independently and average their predictions. Gradient boosting trains trees sequentially, each one correcting the mistakes of previous trees. Both work brilliantly but in different situations.

What makes ensemble methods so powerful

Ensemble learning combines multiple models to produce better predictions than any single model. The wisdom of crowds principle applies: many mediocre models together often beat one sophisticated model.

Think about asking one expert versus polling 100 experts. The single expert might be very knowledgeable but could have blind spots or biases. The 100 experts collectively are more likely to give you a balanced answer. Machine learning ensembles work the same way.

For ensembles to work well, the individual models need to make different kinds of mistakes. If all models fail on the same examples, combining them doesn’t help. But if they fail on different examples, their predictions can balance each other out.

This is why ensembles of decision trees work so well. Individual trees are unstable and overfit, but they overfit in different ways. One tree might split on feature A first while another splits on feature B. Their errors don’t perfectly overlap, so averaging reduces overall error.

The key insight is that variance decreases when you average multiple predictions. Bias doesn’t change much but variance drops significantly. Since decision trees have low bias but high variance, ensembles fix their biggest weakness.

How random forests work

Random forests create diversity among trees through two sources of randomness. First, each tree trains on a different random sample of the training data. This is called bootstrap aggregating or bagging.

Bootstrap sampling means randomly selecting examples with replacement. You might pick the same example multiple times for one tree’s training set while excluding other examples entirely. Each tree sees a slightly different view of the data.

Second, at each split point each tree considers only a random subset of features. Instead of evaluating all features to find the best split, the tree picks a few random features and chooses the best split among those. This forces trees to use different features and prevents all trees from looking identical.

After training all trees independently in parallel, random forests make predictions by averaging all tree outputs for regression or taking a majority vote for classification. Each tree gets equal weight in the final prediction.

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier, RandomForestRegressor

from sklearn.datasets import make_classification

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

import numpy as np

# Create sample data

X, y = make_classification(

n_samples=1000,

n_features=20,

n_informative=15,

random_state=42

)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42

)

# Train random forest

rf = RandomForestClassifier(

n_estimators=100,

max_depth=10,

min_samples_split=5,

random_state=42

)

rf.fit(X_train, y_train)

print(f"Random Forest training accuracy: {rf.score(X_train, y_train):.4f}")

print(f"Random Forest test accuracy: {rf.score(X_test, y_test):.4f}")

Random forests are robust and hard to mess up. They rarely overfit severely even with many trees. Adding more trees improves performance up to a point then plateaus. They handle high-dimensional data well and provide feature importance scores showing which variables matter most.

The main hyperparameters to tune are number of trees, maximum depth, minimum samples per split, and maximum features considered per split. More trees is almost always better but with diminishing returns after a few hundred.

How gradient boosting works

Gradient boosting takes a completely different approach. Instead of training trees independently, it trains them sequentially with each tree learning to correct the mistakes of the previous trees.

The first tree trains on the original data and makes predictions. Some predictions are accurate, others are way off. The second tree trains not on the original targets but on the residuals or errors from the first tree.

The second tree learns patterns in what the first tree got wrong. It becomes specialized at fixing those errors. Add the predictions of both trees together and you get better overall predictions than either tree alone.

This process continues for many iterations. Each new tree trains on the residual errors after combining all previous trees. The final model sums predictions from all trees, with each tree contributing a small correction.

A learning rate hyperparameter controls how much each tree contributes. Small learning rates mean each tree makes small corrections. This requires more trees but often produces better final models by preventing any single tree from dominating.

from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingClassifier

# Train gradient boosting

gb = GradientBoostingClassifier(

n_estimators=100,

learning_rate=0.1,

max_depth=5,

random_state=42

)

gb.fit(X_train, y_train)

print(f"Gradient Boosting training accuracy: {gb.score(X_train, y_train):.4f}")

print(f"Gradient Boosting test accuracy: {gb.score(X_test, y_test):.4f}")

Gradient boosting is more prone to overfitting than random forests because later trees specialize in fixing training errors, which might include noise. Careful tuning of tree depth, learning rate, and number of iterations is essential.

The sequential nature also means training can’t be parallelized like random forests. Each tree must wait for the previous one to finish. This makes gradient boosting slower to train on large datasets.

Key differences between random forest and gradient boosting

Understanding the fundamental differences helps you choose the right algorithm for your situation.

Training approach differs completely. Random forests train all trees independently in parallel. Gradient boosting trains trees sequentially, each depending on previous trees. This makes random forests faster to train on multi-core systems.

Prediction combination differs too. Random forests average independent predictions. Gradient boosting sums sequential corrections. Random forest predictions are more stable while gradient boosting predictions can be more accurate but also more sensitive to training details.

Overfitting behavior differs significantly. Random forests rarely overfit severely. Adding more trees almost never hurts. Gradient boosting can easily overfit if you use too many trees or trees that are too deep. You need to monitor validation performance and stop training at the right point.

Hyperparameter sensitivity differs. Random forests are relatively forgiving. Reasonable default parameters often work decently. Gradient boosting requires more careful tuning of learning rate, tree depth, and number of iterations to achieve good performance.

Computational requirements differ. Random forests train faster by parallelizing tree construction. Gradient boosting trains slower due to sequential dependencies but can use simpler trees to compensate. For prediction, both are similarly fast.

import time

# Compare training times

start = time.time()

rf.fit(X_train, y_train)

rf_time = time.time() - start

start = time.time()

gb.fit(X_train, y_train)

gb_time = time.time() - start

print(f"Random Forest training time: {rf_time:.2f} seconds")

print(f"Gradient Boosting training time: {gb_time:.2f} seconds")

When to use random forest

Random forests excel as your general purpose go-to algorithm for many problems. Use random forests when you want a robust model with minimal tuning that works reasonably well out of the box.

Choose random forests when training speed matters. The parallel training scales well to large datasets and multi-core processors. You can train on millions of examples in reasonable time.

Use random forests when you need stable predictions that don’t change dramatically with small variations in training data. The averaging of many independent trees provides inherent stability.

Random forests work well when you have a dataset with many features, some of which might be irrelevant. The random feature selection at each split means uninformative features get used less often. Feature importance scores help identify which variables actually matter.

For problems where interpretability is important, individual trees in a random forest are still interpretable. You can examine a few trees to understand the kinds of rules being learned even if the full ensemble is complex.

Random forests are also forgiving for beginners. You can get decent results without extensive hyperparameter tuning. The risk of completely messing up your model through poor parameter choices is low.

When to use gradient boosting

Use gradient boosting when you need maximum predictive performance and have time to tune hyperparameters properly. Gradient boosting wins many machine learning competitions because it can squeeze out a few extra percentage points of accuracy.

Choose gradient boosting when your dataset is clean and well-prepared. Boosting is more sensitive to noisy data and outliers because later trees can overfit to these anomalies. Random forests are more robust to messy data.

Gradient boosting works well on medium-sized datasets where you can afford careful validation and tuning. It’s less ideal for massive datasets where the sequential training becomes a bottleneck or tiny datasets where overfitting is a major concern.

Modern implementations like XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost optimize gradient boosting for speed and performance. These libraries add regularization, better handling of missing values, and clever engineering that makes gradient boosting much more practical than the original sklearn implementation.

# Using XGBoost for better gradient boosting

import xgboost as xgb

xgb_model = xgb.XGBClassifier(

n_estimators=100,

learning_rate=0.1,

max_depth=5,

random_state=42

)

xgb_model.fit(X_train, y_train)

print(f"XGBoost test accuracy: {xgb_model.score(X_test, y_test):.4f}")

Use gradient boosting when you’re competing for best performance and willing to invest time in hyperparameter optimization. The payoff is usually worth it for important applications.

Practical recommendation

For most real world projects, start with random forest. It’s fast, robust, and works well with default parameters. Train a random forest baseline before trying anything fancier.

If you need better performance and have time to tune properly, try gradient boosting next. Use one of the modern implementations like XGBoost or LightGBM rather than sklearn’s basic version. Carefully validate to avoid overfitting.

Often the best solution is using both. Train both random forest and gradient boosting models, then ensemble their predictions. Combining these complementary approaches can beat either one individually.

Random forest vs gradient boosting isn’t about one being universally better. They have different strengths and ideal use cases. Understanding both gives you flexibility to choose the right tool for each problem. Ready to put these ensemble methods into a complete workflow? Check out our guide on machine learning pipeline to learn how to chain preprocessing, training, and evaluation into clean, reproducible systems.